Application of probiotics in the prevention and management of ulcerative colitis

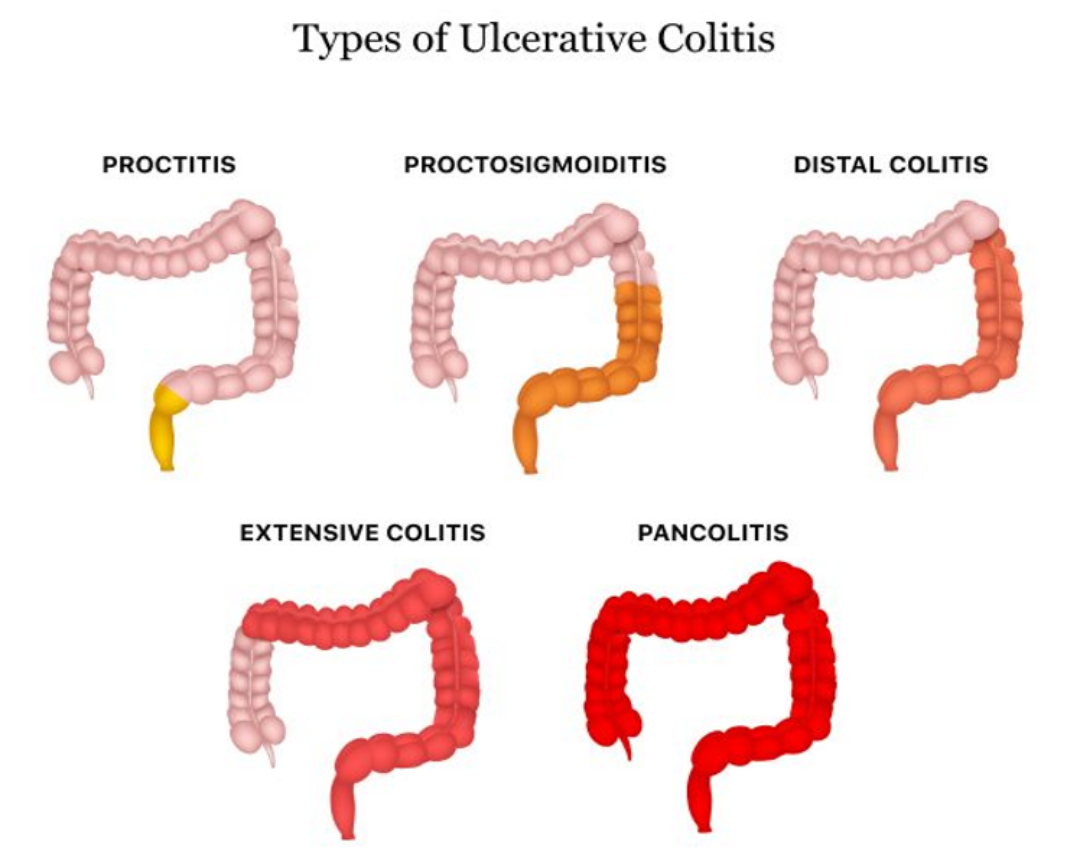

Ulcerative colitis is one of the two major forms of inflammatory bowel disease, and it is a chronic condition that is prone to relapse, with an annual incidence rate of about 10 to 20 per 100,000 people. It is characterized by inflammation of the colon mucosa, increased permeability of the colon tissue, and an increase in white blood cells in the colon [1, 2]. Ulcerative colitis can take different forms (Figure 1) and can occur in people of all ages, but it usually begins between the ages of 15 and 30 and is less common between the ages of 50 and 70. The disease affects both men and women equally and appears to run in families, with reports indicating that up to 20% of people with ulcerative colitis have a family member or relative with the condition. Additionally, about 20% of cases are diagnosed before the age of 20, and the disease can occur in children as young as 2 years old. The significant impact on quality of life necessitates the development of effective therapies to enhance health outcomes. Probiotics are one such effective method [3, 4].

Mechanism of ulcerative colitis

The symptoms of ulcerative colitis tend to worsen over time. Initially, there may be some signs such as fatigue, nausea, and weight loss. Then, the symptoms progress and become more severe, including blood, mucus, or pus in the stool, severe diarrhea, joint pain, and liver disease. The disease mechanism of ulcerative colitis relates to the dysregulation of the immune response of the intestinal mucosa to environmental antigens in the gut, such as the gut microbiota [5]. Ulcerative colitis occurs in the colon, which is home to many gut bacteria. This suggests that the gut microbiota plays an important role in the initiation and maintenance of colitis (Figure 2). The normal gut microbiota consists of about 400 different species of bacteria, with the highest concentration in the distal colon and rectum [6]. The gut microbiota produces harmful compounds such as endotoxins from gram-negative bacteria and harmful enzymes such as β-glucuronidase and tryptophanase, which produce cell-damaging or carcinogenic agents [7]. These cell-damaging toxins and endotoxins can interact with the intestinal mucosa and trigger reactions in the intestinal epithelial cells, producing pro-inflammatory cytokines and other mediators that activate the inflammatory response of the mucosal immune system.

Figure 1: Different forms of ulcerative colitis

Treatment of ulcerative colitis and limitations

Currently, the treatment of ulcerative colitis mainly relies on traditional medications such as aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressive drugs. These drugs reduce the inflammation and decrease the expression of some inflammatory molecules, but their side effects and systemic effects significantly impact the quality of life of patients, especially with long-term use [8, 9]. Therefore, modulating the intestinal microbiota to reduce the inflammatory potential of invading bacteria is a promising approach to ulcerative colitis.

Figure 2: Inflammatory progression of ulcerative colitis

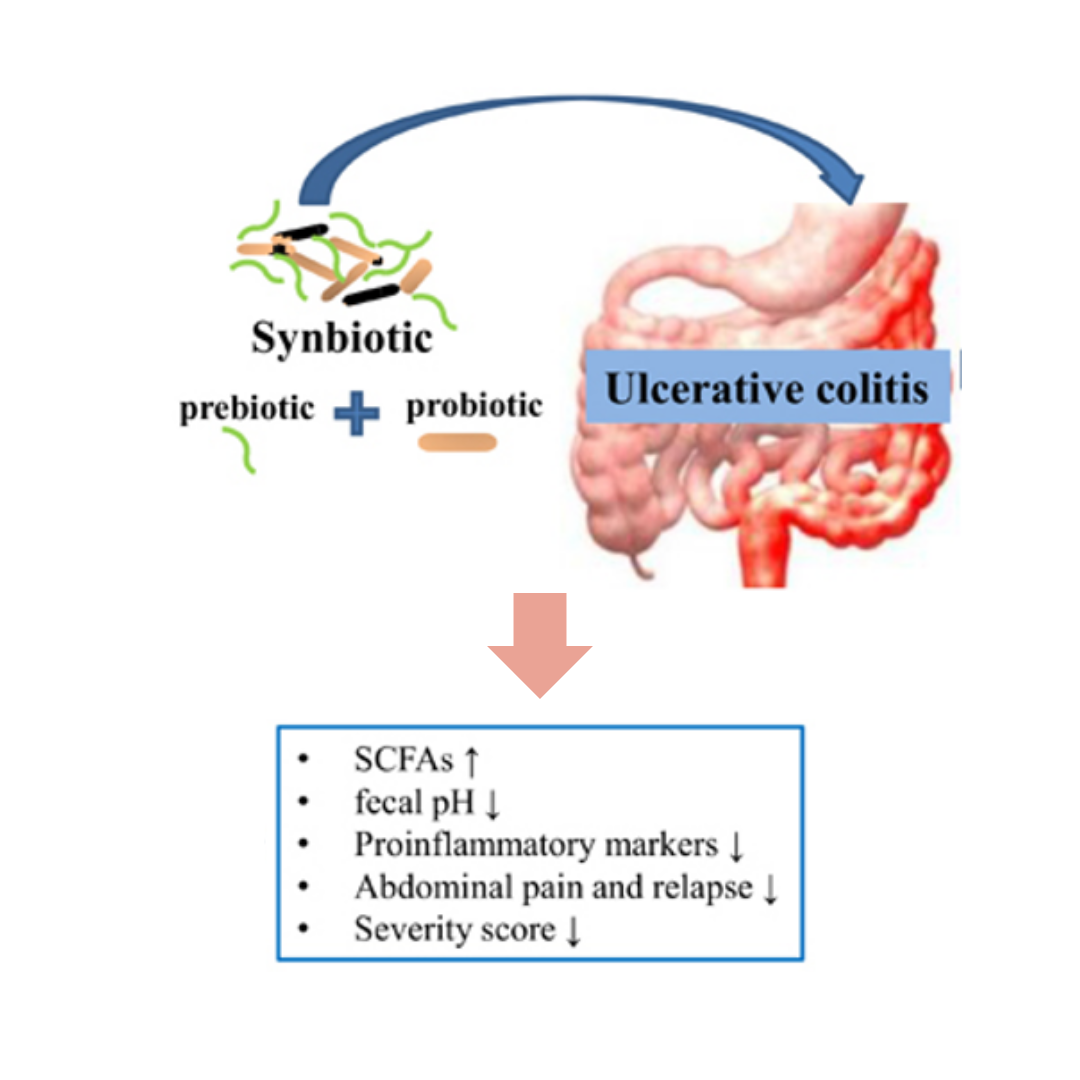

Another approach is the use of beneficial microorganisms to interact with the host tissue to alleviate inflammation. Researchers have defined probiotics as live microorganisms that, when given in sufficient quantities, provide health benefits to the host. They achieve this by balancing the gut microbiota, improving gut dysbiosis, and producing anti-diabetic, lipid-lowering, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory effects, especially in ulcerative colitis (Figure 3) [10-12]. The most widely used probiotic strains in humans are Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli. Many studies have shown that the use of probiotics in combination with conventional therapy for ulcerative colitis can effectively reduce inflammation and improve the quality of life for patients with ulcerative colitis.

Figure 3: Effectiveness of probiotics in the treatment of ulcerative colitis

Mechanisms of probiotics and clinical applications in the treatment of ulcerative colitis

Probiotics act through several different mechanisms. Firstly, they act as a barrier, forming a layer on the surface of the intestinal epithelium and through competitive inhibition, preventing bacteria in the gut lumen from accessing the mucosa and stimulating the mucosal immune system. Secondly, probiotics enhance the production of mucus, which helps protect against invading bacteria and can alter the thickness of the mucus, thus changing the adhesion pattern of bacteria. Thirdly, probiotics stimulate the mucosal immune system in the gut to produce protective immunoglobulins (Ig) such as IgA and a range of defensins, bacteriocins that protect the gut lumen. Finally, probiotics alter the function of the mucosal immune system, increasing its anti-inflammatory capacity and reducing inflammation, specifically by stimulating dendritic cells to be less responsive to bacteria in the gut. These mechanisms appear to be particularly important in ulcerative colitis. By acting through these mechanisms, probiotics can modulate the impact of bacteria in the gut by causing and maintaining the inflammatory response in the gut [12].

Several probiotic formulations and their formulas have been studied for both the induction and maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis, primarily Escherichia coli and VSL#3, which have been shown to provide significant benefits for the prevention and treatment of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis [11-14]. Probiotic E. coli Nissle has been compared to mesalamine in some trials, and both treatments have been equally effective. Researchers have not directly compared VSL#3 to mesalamine, but studies on VSL#3 have concluded that the rate of improvement in disease status is similar to that of mesalamine. With these results, the data suggests that if patients use the correct dosage of these probiotics, the effectiveness of both E. coli Nissle and VSL#3 can be similar to that of mesalamine. Some studies have compared the effectiveness of probiotics to placebos and have yielded positive results [1, 5, 15].

According to these studies, probiotics help improve disease status equivalent to the use of placebos or specialized drugs (5-aminosalicylates, sulphasalazine, or corticosteroids) in patients with active ulcerative colitis [16, 17]. Some studies have concluded that probiotic treatment of ulcerative colitis is more effective than placebos in maintaining remission and preventing relapse [2, 18]. The long-term effects of probiotics in the treatment of ulcerative colitis, with clinical studies showing positive results with all patients undergoing combination therapy, have shown better improvement compared to the control group. In particular, the beneficial effects of probiotics were evident even after two years of treatment [19].

Prospects of probiotic technology in the treatment of ulcerative colitis

The cause and pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis, a chronic and relapsing disease, remain unclear as of now. The gut microbiota closely relates to the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis, although researchers have not yet determined the exact bacteria responsible for causing the disease. Using probiotics in the treatment of ulcerative colitis is still under investigation. Probiotics can help normalize the dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, improve the gut microecological environment, enhance the function of the gut mucosal barrier, and reduce gastrointestinal infections. Researchers have found that probiotics offer an effective approach in treating ulcerative colitis and have the potential to improve the quality of life of patients. However, researchers need to conduct further studies to address issues such as dosage, survival of probiotic strains, lack of standardization, and safety concerns.

References

- Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z., et al., Probiotics for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2020. 3(3): p. CD007443.

- Sang, L.X., et al., Remission induction and maintenance effect of probiotics on ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol, 2010. 16(15): p. 1908-15.

- Do, V.T., B.G. Baird, and D.R. Kockler, Probiotics for maintaining remission of ulcerative colitis in adults. Ann Pharmacother, 2010. 44(3): p. 565-71.

- Conen, A., et al., A pain in the neck: probiotics for ulcerative colitis. Ann Intern Med, 2009. 151(12): p. 895-7.

- Benno, P., et al., Functional alterations of the microflora in patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol, 1993. 28(9): p. 839-44.

- Binder, V., Epidemiology of IBD during the twentieth century: an integrated view. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2004. 18(3): p. 463-79.

- Rhodes, J.M., et al., Faecal mucus degrading glycosidases in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut, 1985. 26(8): p. 761-5.

- Katz, J.A., Advances in the medical therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2002. 18(4): p. 435-40.

- Panaccione, R., J.G. Ferraz, and P. Beck, Advances in medical therapy of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 2005. 5(6): p. 566-72.

- Tabuchi, M., et al., Antidiabetic effect of Lactobacillus GG in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 2003. 67(6): p. 1421-4.

- Chibbar, R. and L.A. Dieleman, Probiotics in the Management of Ulcerative Colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol, 2015. 49 Suppl 1: p. S50-5.

- Fedorak, R.N., Probiotics in the management of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y), 2010. 6(11): p. 688-90.

- Miele, E., et al., Effect of a probiotic preparation (VSL#3) on induction and maintenance of remission in children with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol, 2009. 104(2): p. 437-43.

- Bibiloni, R., et al., VSL#3 probiotic-mixture induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol, 2005. 100(7): p. 1539-46.

- Mullner, K., et al., Probiotics in the management of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Curr Pharm Des, 2014. 20(28): p. 4556-60.

- Kaur, L., et al., Probiotics for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2020. 3(3): p. CD005573.

- Mallon, P., et al., Probiotics for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2007(4): p. CD005573.

- Hegazy, S.K. and M.M. El-Bedewy, Effect of probiotics on pro-inflammatory cytokines and NF-kappaB activation in ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol, 2010. 16(33): p. 4145-51.

- Palumbo, V.D., et al., The long-term effects of probiotics in the therapy of ulcerative colitis: A clinical study. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub, 2016. 160(3): p. 372-7.