Dental Pulp Stem Cell Application in COVID-19 Treatment

The coronavirus disease 2019, originating from Wuhan, China, is known to cause severe respiratory symptoms. The emergence of a cytokine storm in the lungs is evaluated as a crucial step in the pathogenesis mechanism as it causes pathological damage, pulmonary edema, and acute respiratory distress syndrome, potentially leading to death. Currently, there is no treatment method targeting the cytokine storm and assisting in the regeneration of damaged tissue. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are known to play roles as candidates for anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory effects and activating intrinsic regeneration. Therefore, MSC therapy is a potential treatment method for COVID-19. Clinical-grade MSC infusion into the veins of COVID-19 patients may induce immune modulation with improved lung function. Researchers consider dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) as a potential source of MSCs for immune modulation, tissue regeneration, and clinical applications [1].

Mechanism of MSCs Potential in COVID-19 Treatment

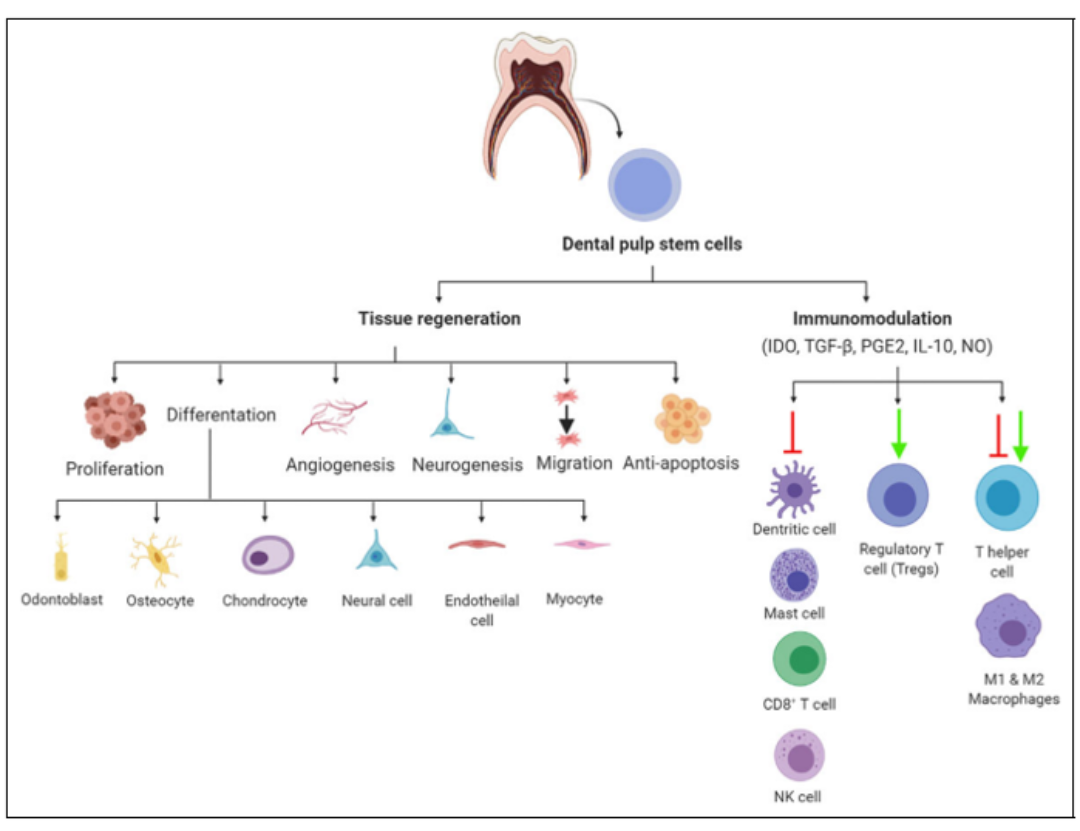

Several studies have demonstrated inflammatory markers through immune intermediaries, interleukins, neutrophil chemoattractant proteins, and necrosis factors play crucial roles in the pathogenic mechanism of COVID-19 [2] [3]. Death occurs as a result of the presence of these cytokines in lung cells, leading to edema, lung dysfunction, and acute respiratory distress [3]. The progression of COVID-19 is accompanied by a decrease in lymphocytes and a significant increase in neutrophils [4]. The number of B cells, T cells, and NK cells decreases in patients with severe infections [4]. Until now, treatment measures mainly aim at minimizing the spread of infection. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are believed to support COVID-19 treatment through two strategies: immune modulation of immune cells and inflammation reduction [5] and regeneration of damaged tissues [6]. Researchers can isolate MSCs from various sources, among which dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) are known for their unique immune modulation and regeneration properties [7].

Figure 1: Mechanism of MSCs application in COVID-19 Treatment

MSCs are multipotent stem cells originating from mesenchymal tissues expressing various surface markers (CD90, CD105, CD29, CD44, CD54, CD166, Stro-1, and MHC-I) and showing the absence of hematopoietic markers (CD45, CD31, CD11b, CD19, CD34, CD14, and HLA-DR) [8] [9]. MSCs have been extensively studied for over 30 years. They possess the ability to release beneficial growth factors and cytokines. MSCs exhibit effective anti-inflammatory properties and immune-modulatory characteristics that can treat inflammatory and immune-mediated conditions [10]. Additionally, MSCs have antibacterial properties that reduce acute lung injury (ALI) caused by bacterial infections [11].

Potential Mechanism of DPSCs in COVID-19 Treatment

DPSCs are the most common type of MSCs isolated from dental pulp with unique biological characteristics [12]. This makes DPSCs highly promising agents. DPSCs have efficient immune-modulatory functions based on the release of soluble factors such as indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), transforming growth factor beta (TGF-b), and human leukocyte antigen G5 (HLA-G5) [13]. Furthermore, DPSCs inhibit the pro-inflammatory function of M1 macrophages by suppressing TNF-a secretion through the IDO intermediate pathway [14]. Moreover, they polarize macrophages towards the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype by increasing IL-10, PGE2, IL-6, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) secretion [14]. Additionally, they have the ability to inhibit Th17 cell activation and promote the development of T cells, CD 25, and CD 4 [15]. At the humoral immune level, DPSCs impede the proliferation, antibody production, and differentiation ability of B cells and suppress the proliferation of T and B cells by releasing TGF-b1 [16]. DPSCs play a crucial role in tissue regeneration and have the ability to repair various tissue disorders [17].

Figure 2: Diagram of the Potential Mechanism of DPSCs in COVID-19 Treatment

Structural differences in alveoli, inflammation accumulation in mature cells, and fibrosis are the main characteristics of progressive acute respiratory distress syndrome. The activation of macrophages plays a crucial role in the pathogenic factor, wherein M1 macrophages release pro-inflammatory cytokines and promote tissue fibrosis [18]. In studies on COVID-19 treatment methods, MSCs have been directly injected into the bloodstream, and fortunately, these MSCs are predominantly retained in the lungs, the organ most affected. This suggests that injecting DPSCs into the bloodstream will mainly localize in the lungs [19]. Compared to other sources of MSCs, DPSCs demonstrate a higher potential for COVID-19 treatment for the following reasons:

- DPSCs can be easily isolated in a less invasive manner from extracted teeth [20]

- DPSCs are abundant, easy to harvest, and have effective therapeutic capabilities [12]

- DPSCs show high proliferation potential, capable of providing a large number of cells in a short time [21]

However, there are certain limitations when using DPSCs, such as losing their characteristics after a certain number of sub-cultures [1].

COVID-19 is a global pandemic that requires the simultaneous development of effective therapies and vaccines. One of the most notable findings about COVID-19 is the presence of a cytokine storm in the lungs of severely affected patients. Scientists have widely employed MSCs in other immune-related diseases. MSCs, specifically DPSCs, could be excellent candidates for treating this novel disease due to their ability to inhibit cytokine release through immune modulation and their regenerative potential.

References:

- Zayed, M. and K.J.C.t. Iohara, Immunomodulation and regeneration properties of dental pulp stem cells: a potential therapy to treat coronavirus disease 2019. 2020. 29: p. 0963689720952089.

- Huang, C., et al., Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. 2020. 395(10223): p. 497-506.

- Metcalfe, S.M.J.M.i.d.d., Mesenchymal stem cells and management of COVID-19 pneumonia. 2020. 5: p. 100019.

- Chuan, Q., et al., Dysregulation of immune response in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. 2020. 10.

- Prockop, D.J.J.C., The exciting prospects of new therapies with mesenchymal stromal cells. 2017. 19(1): p. 1-8.

- Wang, S., et al., First stem cell transplantation to regenerate human lung. 2018. 9(3): p. 244-245.

- Yamada, Y., et al., Clinical potential and current progress of dental pulp stem cells for various systemic diseases in regenerative medicine: a concise review. 2019. 20(5): p. 1132.

- Young, H.E., et al., Human pluripotent and progenitor cells display cell surface cluster differentiation markers CD10, CD13, CD56, and MHC class-I. 1999. 221(1): p. 63-72.

- Trusler, O., et al., Cell surface markers for the identification and study of human naive pluripotent stem cells. 2018. 26: p. 36-43.

- Gomez-Salazar, M., et al., Five decades later, are mesenchymal stem cells still relevant? 2020. 8: p. 148.

- Lee, J.W., et al., Therapeutic effects of human mesenchymal stem cells in ex vivo human lungs injured with live bacteria. 2013. 187(7): p. 751-760.

- Huang, G.-J., S. Gronthos, and S.J.J.o.d.r. Shi, Mesenchymal stem cells derived from dental tissues vs. those from other sources: their biology and role in regenerative medicine. 2009. 88(9): p. 792-806.

- Li, Z., et al., Immunomodulatory properties of dental tissue‐derived mesenchymal stem cells. 2014. 20(1): p. 25-34.

- Zhang, Q., et al., Human oral mucosa and gingiva: a unique reservoir for mesenchymal stem cells. 2012. 91(11): p. 1011-1018.

- Ding, G., J. Niu, and Y.J.H.C. Liu, Dental pulp stem cells suppress the proliferation of lymphocytes via transforming growth factor-β1. 2015. 28: p. 81-90.

- Zhao, Y., et al., Fas ligand regulates the immunomodulatory properties of dental pulp stem cells. 2012. 91(10): p. 948-954.

- Morsczeck, C., et al., Comparison of human dental follicle cells (DFCs) and stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED) after neural differentiation in vitro. 2010. 14: p. 433-440.

- Wynn, T.A. and T.R.J.N.m. Ramalingam, Mechanisms of fibrosis: therapeutic translation for fibrotic disease. 2012. 18(7): p. 1028-1040.

- Barbash, I.M., et al., Systemic delivery of bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells to the infarcted myocardium: feasibility, cell migration, and body distribution. 2003. 108(7): p. 863-868.

- Iohara, K., et al., Side population cells isolated from porcine dental pulp tissue with self‐renewal and multipotency for dentinogenesis, chondrogenesis, adipogenesis, and neurogenesis. 2006. 24(11): p. 2493-2503.

- Miura, M., et al., SHED: stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. 2003. 100(10): p. 5807-5812.