Probiotics Applications in Urinary Tract Infections Treatment

Urinary tract infection infects one or more parts of the urinary system, such as the kidneys, bladder, and urethra. This is a highly prevalent condition; according to the Global Burden of Disease project, there were over 40.461 million reported cases in 2019, with 23.790 fatalities and an average of 520,200 new cases daily (1). Urinary tract infections can be categorized based on various criteria, such as the location of the infection: upper (kidneys) or lower (bladder, urethra, prostate gland), or based on the presence of complications and the recurrence of the disease (Figure 1). The condition can affect individuals of all ages. According to research by the European Association of Urology (EAU), urinary tract infections are more common in women, with 1 in 3 women experiencing urinary tract infection before the age of 24 and nearly half of all women having at least one episode of urinary tract infection in their lifetime (2).

Symptoms of urinary tract infections often include painful urination, frequent urination with only a small amount of urine, fever, or chills. Serious complications may arise, such as bloodstream infections and kidney damage. In pregnant women, urinary tract infections can increase the risk of pregnancy-related complications, such as preterm birth and miscarriage. Poor hygiene, urinary tract abnormalities, bacterial infection through sexual intercourse, or surgical interventions in the urinary tract can cause urinary tract infections. The common treatment method currently involves the use of antibiotics. Additionally, vaccination and, notably, the use of probiotics for prevention and in combination with treatment are gaining strong recognition.

Figure 1: Urinary system and urinary tract infection caused by bacteria.

Treatment and Prevention of Urinary Tract Infections Treatment and Prevention

The use of antibiotics in treating urinary tract infections is a traditional and common method. The bacteria responsible for infections are often E. coli, accounting for up to 80%, with the remaining caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae (7%), Proteus mirabilis, and fungi (5%) (4). Therefore, commonly prescribed antibiotics include amoxicillin, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, and ciprofloxacin. These antibiotics have high concentrations excreted in urine, making them suitable for treating urinary tract infections. Among them, ciprofloxacin, with over 80% excretion through urine, is specifically indicated for treating severe symptoms. Amoxicillin and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, with lower excretion rates (>40%), are usually prescribed for patients with moderate or mild symptoms. However, antibiotic use should be under a doctor’s prescription, as misuse can lead to bacterial resistance and side effects. Currently, the combination of antibiotic and probiotic treatment is being strongly applied to enhance treatment efficacy, reduce antibiotic usage duration, and decrease the likelihood of recurrence.

The Role of Probiotics in the Prevention and Treatment of Urinary Tract Infections

The primary cause of lower urinary tract infections is bacterial infection from the digestive and reproductive systems, given their proximity to the body structure. This is particularly evident in women with short and straight urethra, making it easy for bacteria to ascend to the bladder and kidneys from the lower urinary tract. Therefore, urinary tract infections have a close relationship with vaginal infections caused by bacteria and fungi. A healthy vaginal microbiome can prevent urinary tract diseases (7). Prolonged use of antibiotics for treatment can disrupt the microbial balance in the urinary and vaginal systems. Probiotics play a significant role in balancing and restoring the microbial ecosystem (Figure 2). Furthermore, researchers and healthcare professionals have extensively studied and emphasized probiotics as an alternative treatment method due to their ability to be used for an extended period with minimal side effects. Lactobacillus, the most commonly used probiotic strain, undergoes extensive study and application in the treatment of urinary tract infections. Their crucial role lies in preventing invasion, inhibiting the growth of harmful microorganisms by stimulating the immune system, producing antimicrobial substances (H2O2 and bacteriocins, lactic acid), forming a biofilm, competing for nutrients, adhering to harmful microorganisms, and blocking bacterial toxins (8).

Figure 2: The role of probiotics in combating pathogenic bacteria in the urinary system (1)

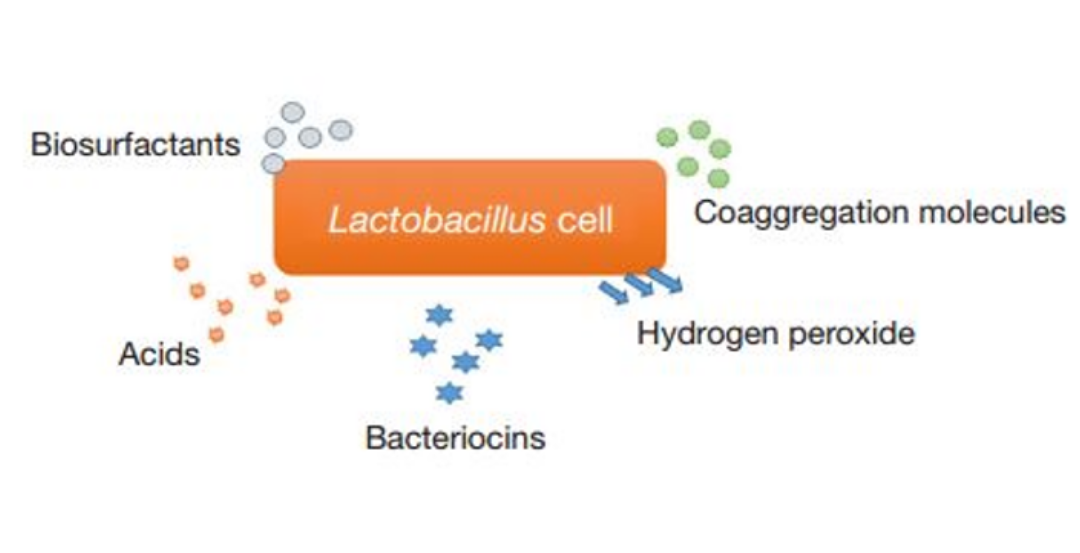

Probiotics, especially strains of Lactobacillus, play a crucial role in maintaining the microbial balance in the host. Particularly, they can regulate immune responses by interacting with cells lining the urinary tract to produce antibodies (13). The ability to form a biofilm helps these beneficial Lactobacillus strains sustainably develop within the mucosa and gain an advantage over disease-causing microorganisms (14). Lactobacillus strains have the ability to produce surface-cleansing substances (biosurfactants) that hinder the adhesion of disease-causing bacteria. For example, two strains, L. acidophilus and L. fermentum, can produce surfactin molecules, inhibiting the adhesion of most E. coli strains, causing urinary tract inflammation (15). Organic acids released by Lactobacillus, such as lactic acid and propionic acid, help reduce the vaginal pH, thereby inhibiting most pathogenic microorganisms (16). L. crispatus and L. jensenii are found in the vagina of 96% of healthy women, compared to only 3.5% in women with vaginal inflammation (17).

Figure 3: Biological products from Lactobacillus help counteract disease-causing microorganisms (1)

Many strains of Lactobacillus have been evaluated and tested in the treatment of urinary and vaginal tract infections (Figure 3). Among them, strains such as L. rhamnosus GR-1, L. reuteri B-54, L. reuteri RC-14, L. casei shirota, and L. crispatus CTV-05 have shown the most promising results in urinary tract infection trials. A study by Reid and colleagues in 1992 revealed that using two strains, L. rhamnosus GR-1 and L. reuteri B-54, on 41 urinary tract infection patients reduced the recurrence rate, with only 21% of patients using probiotics experiencing a relapse compared to 41% in the non-user group (10). A 2019 study by Anukam and colleagues using L. rhamnosus GR-1 and L. reuteri B-54 for acute urinary tract infection patients helped reduce cytokine levels such as TNF-alpha, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 compared to patients not using probiotics. Regulating these cytokines improves treatment outcomes, avoiding an excessive immune response leading to increased inflammation (9). The combination of L. rhamnosus GR-1 and L. reuteri RC-14 with metronidazole for women with vaginal inflammation helped achieve a 65% recovery rate within 30 days, compared to 33% of patients using metronidazole alone (11). A study by Stapleton in 2011 using L. crispatus CTV-05 on 100 adult women with mild urinary tract infections or at least one prior treatment showed that the probiotic group, continuously using probiotics for five days and then once every 10 weeks, had a recurrence rate of only 15%, compared to the control group with a rate of 27% (12).

In conclusion, through numerous studies and evaluations, probiotics have significant potential for use in treating and preventing urinary tract infections due to their outstanding advantages, such as allowing long-term use, being non-toxic, and enhancing immunity. Scientific research on the application of probiotics in urinary tract infection treatment is extensive and ongoing. However, the treatment and use of probiotics, including dosage, duration, and suitable candidates, should have specific guidance from a medical professional.

References:

- Das, S., & Ameeruddin, S. (2022). Probiotics in common urological conditions: a narrative review.

- Grabe M, Bartoletti R, Bjerklund Johansen TE, et al. EAU Guidelines on Urological Infections. 2015, http://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/19-Urological-infections_LR2.pdf.

- Wagenlehner, F. M., & Naber, K. G. (2006). Treatment of bacterial urinary tract infections: presence and future. European urology, 49(2), 235-244.

- Terlizzi, M. E., Gribaudo, G., & Maffei, M. E. (2017). UroPathogenic Escherichia coli (UPEC) infections: virulence factors, bladder responses, antibiotic, and non-antibiotic antimicrobial strategies. Frontiers in microbiology, 8, 1566.

- Bauer, H. W., Rahlfs, V. W., Lauener, P. A., & Bleßmann, G. S. (2002). Prevention of recurrent urinary tract infections with immuno-active E. coli fractions: a meta-analysis of five placebo-controlled double-blind studies. International journal of antimicrobial agents, 19(6), 451-456.

- Riedasch, G., & Möhring, K. (1986). Immunisierungstherapie rezidivierender Harnwegsinfekte der Frau. Therapiewoche, 10, 896-900.

- Reid, G., & Bruce, A. W. (2003). Urogenital infections in women: can probiotics help?. Postgraduate Medical Journal, 79(934), 428-432.

- Reid, G., & Burton, J. (2002). Use of Lactobacillus to prevent infection by pathogenic bacteria. Microbes and infection, 4(3), 319-324.

- Anukam, K. C., Hayes, K., Summers, K., & Reid, G. (2009). Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14 may help downregulate TNF-Alpha, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and IL-12 (p70) in the neurogenic bladder of spinal cord injured patient with urinary tract infections: a two-case study. Advances in urology, 2009.

- Reid, G., Bruce, A. W., & Taylor, M. (1992). Influence of three-day antimicrobial therapy and lactobacillus vaginal suppositories on recurrence of urinary tract infections. Clinical therapeutics, 14(1), 11-16.

- Anukam, K., Osazuwa, E., Ahonkhai, I., Ngwu, M., Osemene, G., Bruce, A. W., & Reid, G. (2006). Augmentation of antimicrobial metronidazole therapy of bacterial vaginosis with oral probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GR-1 and Lactobacillus reuteri RC-14: randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Microbes and Infection, 8(6), 1450-1454.

- Stapleton, A. E., Au-Yeung, M., Hooton, T. M., Fredricks, D. N., Roberts, P. L., Czaja, C. A., … & Stamm, W. E. (2011). Randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial of a Lactobacillus crispatus probiotic given intravaginally for prevention of recurrent urinary tract infection. Clinical infectious diseases, 52(10), 1212-1217.

- Isolauri, E., Sütas, Y., Kankaanpää, P., Arvilommi, H., & Salminen, S. (2001). Probiotics: effects on immunity. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 73(2), 444s-450s.

- Ocaña, V. S., & Nader-Macías, M. E. (2002). Vaginal lactobacilli: self-and co-aggregating ability. British journal of biomedical science, 59(4), 183-190.

- Morais, I. M. C., Cordeiro, A. L., Teixeira, G. S., Domingues, V. S., Nardi, R. M. D., Monteiro, A. S., … & Santos, V. L. (2017). Biological and physicochemical properties of biosurfactants produced by Lactobacillus jensenii P 6A and Lactobacillus gasseri P 65. Microbial cell factories, 16, 1-15.

- Boskey, E. R., Telsch, K. M., Whaley, K. J., Moench, T. R., & Cone, R. A. (1999). Acid production by vaginal flora in vitro is consistent with the rate and extent of vaginal acidification. Infection and immunity, 67(10), 5170-5175.

- Eschenbach, D. A., Davick, P. R., Williams, B. L., Klebanoff, S. J., Young-Smith, K., Critchlow, C. M., & Holmes, K. K. (1989). Prevalence of hydrogen peroxide-producing Lactobacillus species in normal women and women with bacterial vaginosis. Journal of clinical microbiology, 27(2), 251-256.